Inshore anglers consider tides and currents a critical factor, but offshore anglers often miss the boat.

Fact: We know that currents have a huge impact on how and when fish feed. Another fact: few offshore anglers take currents into account. This is especially surprising since inshore anglers often have their current considerations honed to fine art, and time their arrival at different hotspots to coincide with the desired water movement at any given time. And nobody’s about to argue that taking this tact is ineffective. So, what gives when it comes to bluewater fishing?

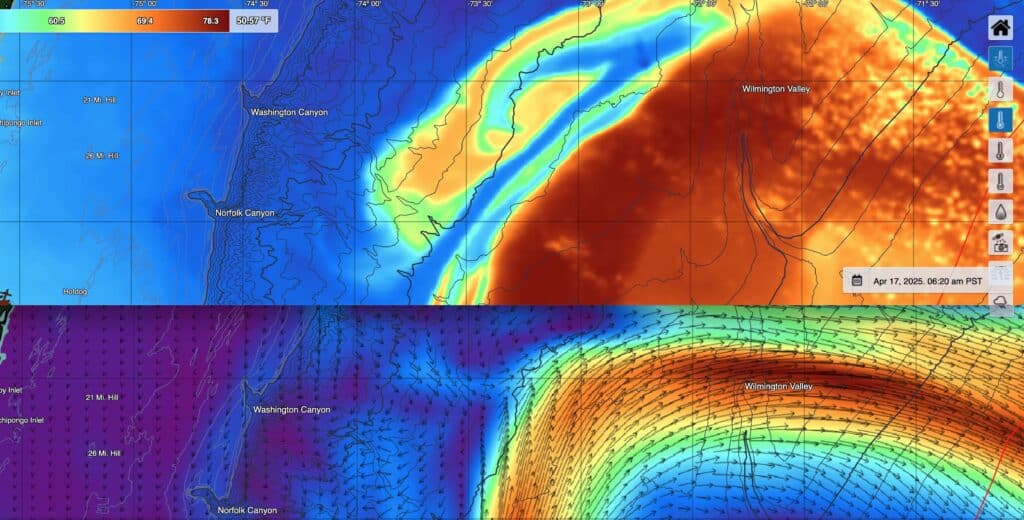

Unfortunately, much of the time, the direction and strength of ocean currents affecting the areas where pelagic species roam isn’t nearly as predictable as the clockwork-like ins and outs of tidal-generated inshore currents. Sure, we know the Gulf Stream is headed north. But beyond that, eddies and swirls can make for some very surprising conditions. You might encounter a northbound current 20 miles off the beach, a westbound current 30 miles out, a southbound current 40 miles out, and so on. Worse, on the open ocean the surface currents and the deepwater currents can be entirely different. And worse yet, these can all change on a daily basis. The real question, however, is if you’re taking this factor into account when you choose where to set out your baits.

Smash Factor

One big reason to take currents into account is that they can jumpstart the food chain where they run into things. Inshore guys know that a point jutting out into a current is going to be hot—but often on only one tide or the other, when the direction of water movement is ideal. The basic concept is no different in the open ocean, whether you’re fishing a canyon, over a sea mount, or over a wreck.

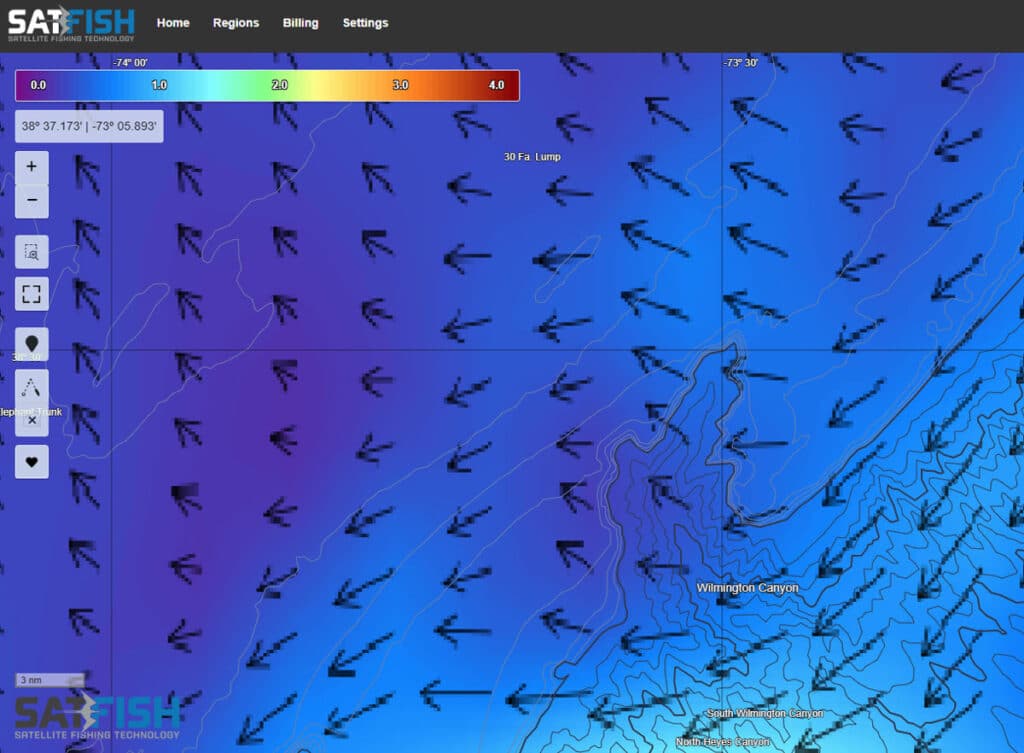

As a general rule of thumb, the side of any obstruction that’s being smacked by a current is likely to have better action than the down-current side. So if you pull up Satfish, check out the current maps, and see that the hump you heard yellowfin were feeding at is being hit by a southbound current, check the northern edges first. Similarly, when fish might be scattered up and down the shelf and you see an area where the currents shift and intersect, that area is likely a better bet than the zones where current is running parallel to the structure. Yes other factors do come into play, and no this isn’t a hard rule. But it does give you a better chance of finding the fish faster when you choose your starting point for the day.

Along with the direction of the current and where it intersects with structure, also look for the zones where currents collied and intersect. Flip from the current maps to the temperature charts, and you’ll notice that often (though not always) these coincide. The more abrupt the collision between water bodies the better. And when these factors all come together and you can locate colliding currents smacking into structure, it’s time to lay in a waypoint.

Predicting the Pelagics

Another critical way to consider currents is in predicting where the fish will be day to day or week to week. Let’s say you just got back from a day of awesome mahi fishing at Spot X, where there was a huge stretch of weeds. Two days later you go back and the weedline’s long gone. If there was a northbound current pushing along at two knots (and a strong breeze isn’t in play) that weedline could have moved 48 miles since you were last there.

Of course, there are almost always confounding factors like wind or colliding currents coming in from other directions. But if you’d been checking the Satfish current and wind maps when you were stuck back on land, you could have looked to see just what was hitting Spot X and made a reasonably good guess as to where the weedline—and the mahi—are likely to have headed. You could also scan the temp charts and look for plankton fronts, additional indications of where the water bodies are colliding and currents are interacting.

Funny side note: back in the late 90s we encountered a big yellow kitchen refrigerator floating near Washington Canyon. It was loaded with mahi and triggerfish, had a few wahoo around it as well, and we spent our entire afternoon fishing it. The next day a buddy down the dock told me about his cool find at Poorman’s Canyon, 26 miles up the coast. Yup, a yellow refrigerator. Two days later the infamous mahi-fridge was found near the Wilmington, another 40-plus miles up the shelf.

Those currents can move stuff and move it fast. They trigger bites, and shut ‘em down. Start keeping tabs on where they’re going and what they’re hitting, and you’ll put more fish into the boat.