Daytime swordfish fishing is no small endeavor, but the potential payoff is utterly spectacular.

You want to try daytime sword fishing in the Wilmington-to-Norfolk zone? There’s a serious method to this madness — doing it right is anything but simple, and doing it wrong leads to long boat rides, hours of boredom, and massive tangles. That said, when you do get it nailed down you’ll hit the docks like Mr. Hero Man. Here’s how to make it happen.

The Rigging

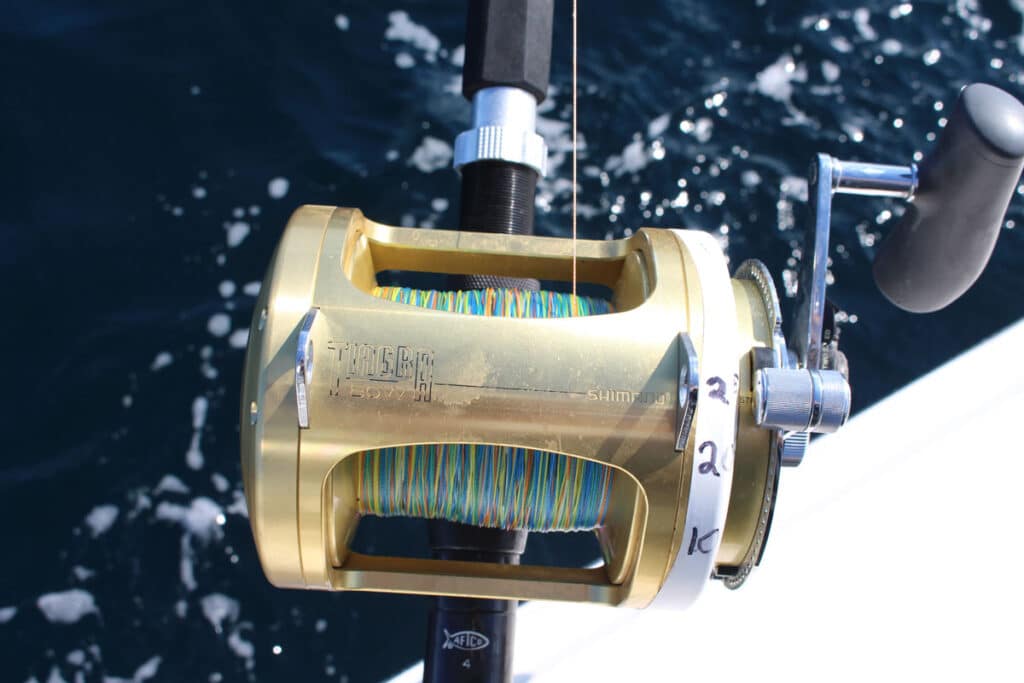

You’ll need some specialized gear for daytime swording, starting with a bent-butt 80- to 130-class swording rod with a soft tip. The bent butt is a must because the rod will spend most of its time in the gunwale (just try holding a rod dangling 1500 feet of line and a 10-pound weight for 20 minutes if you don’t believe it), and a soft tip is needed to watch for bites because a visual indication is how you’ll know when and how to react (more about that later).

Reels should be spooled with 80- to 100-pound braid that’s color-coded to indicate length so you can keep track of the bait’s depth. The reel either needs to be an electric or you’ll want a “reel cranky” (a fitting that you can add to a power drill to spin the reel handle) or similar device. This goes even if you plan to hand-crank the fish, because reeling up by hand after missed bites or to move locations will take forever and a day.

The mainline gets topped off with 120’ or so of 120- to 200-pound wind-on mono leader terminating with a wind-on swivel. At 100’ from the swivel use heavy wax rigging floss to add a loop for attaching a longline clip with your weight, generally a 10-pound sash weight on a five-foot dropper line. At 30’ from the swivel, bend on a strand of copper with a loop to attach a deep-drop strobe LED light. The copper should be tight enough to hold the strobe in place, but loose enough that when you reel it to the rod tip the line can pass through and you can keep cranking.

Rigs consist of five-foot bite-leaders of 200- to 300-pound test with skirted rigged eels, strip baits, or rigged squid on 12/0 hooks. What kind of hooks? We could argue all day about it but there are plenty of sharpies out there who insist on using circle hooks and plenty of others who say J hooks are the way to go. Pick your poison.

Choosing the Spot

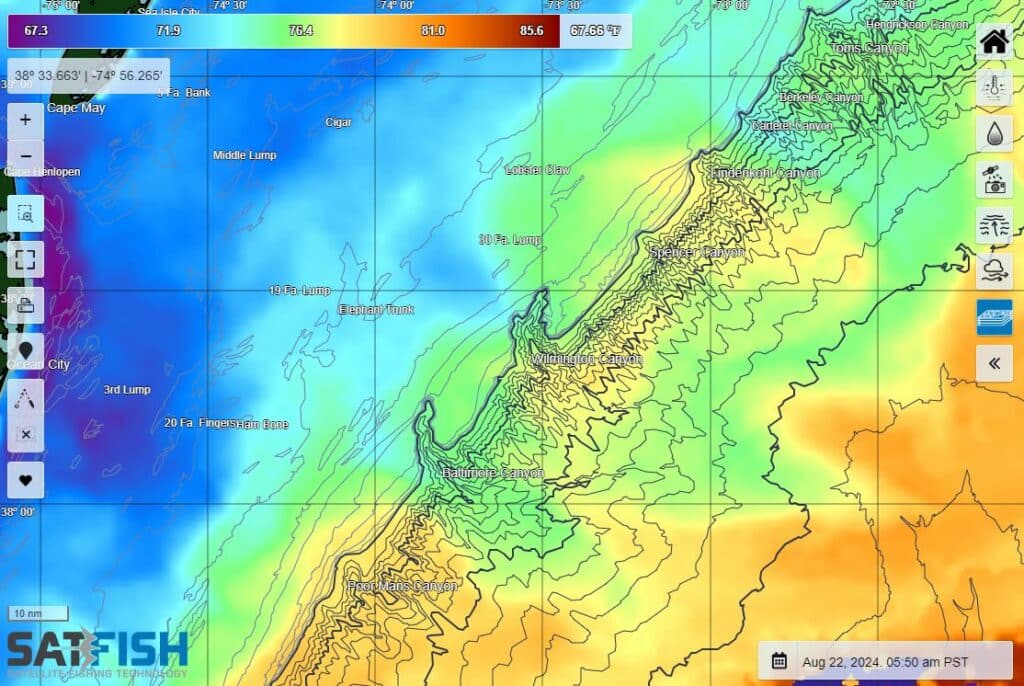

As is always the case with fishing, structure is a good thing. Not just the structure of the canyon walls but also temperature breaks, so check out SatFish and look for those water barriers and eddies. Areas where a strong break intersects with a sharp drop in the shelf should be considered prime.

Most daytime swording takes place in 1000’ to 2000’ with 1500-ish depths often being a sweet spot. Chinks and bulges in the edge of the shelf are a good thing, as you want to pick a location where the current gets interrupted. If you try a drift on one side of a canyon bight and go biteless, it’s generally a good idea to shift to the far opposite side where currents are likely to be very different.

Making the Drop

Here’s where things get really tricky. Drop that rig wrong and in an hour or two you’ll reel up a snarled mess. Do it right, and potential glory awaits. But before you even get started, shift into neutral for a few minutes and watch the chartplotter to figure out your drift pattern.

With that line on the chartplotter established, turn and point the bow into the prevailing current/wind so you’re going directly up-drift at idle speed. Begin paying out the rig and leader until reaching the floss loop, then clip on the dropper line and weight. Continue idling forward as you pay out the mainline, watching the colored braid to track how much is out. When you hit 200’ lock the reel up for 10 or 12 seconds to remove excess slack from the line. Keep paying out line and stopping it briefly every 200’ to eliminate slack. When you have let out enough line to reach 100’ above bottom, stop letting it out.

At this point turn the boat to the side the line’s deployed from until going 180-degrees in the other direction. Idle back towards the bait until the line is nearly vertical, then spin the wheel so the boat sits beam-to on the down-current/wind side of the bait. Allow a minute or two for the rig to settle, then open up the reel and let the weight fall until it hits bottom. When it touches down crank back up 100’ or so. Piece of cake… right?

Baiting and Battling Swordfish

With your bait deployed, your most critical job now becomes staring at the rod tip. Having two people watch it is a good move to be dang sure you don’t miss a hit when someone gets distracted. Watch how the rod tip responds to the boat’s rocking and rolling, until you (hopefully) see a bob, dip, or twitch that’s out of rhythm with the usual motion. When you see it, immediately go into freespool and let the weight fall to bottom.

As the weight falls watch that braid. You know about how far bottom is and how much line should go out before the weight hits, so if it stops short you know the fish has the bait. And with 10 pounds of lead in freefall, there’s an excellent chance the hook is already set. Crank for all you’re worth until there’s tension on the line and the fight is on.

If the weight falls all the way to the bottom, crank it back up 100’ and start staring at the tip again. Often the swordfish will be giving chase and there’s a strong possibility of a follow-up strike. If that tip jiggles, go right back to freespool and run through the process again. With a skirted eel or a strip bait nine times out of 10 it will still be in fishable shape and if you don’t get a follow-up, you can keep fishing. But if you’ve deployed a soft bait like a rigged squid, there’s a good chance it’s been mauled and needs to be replaced.

Okay: you’ve got a daytime sword on the line? Congratulations, you’ve made it a l-o-n-g way up the mountain, but you haven’t reached the summit just yet. Now you’ve got to get that fish to the boat. Don’t let up for one second if it seems like the fish is barely fighting or maybe came off the hook, because quite often the swordfish will be more confused than anything else at this point. It’s not uncommon for fish weighing hundreds of pounds to allow themselves to be led along like a pup.

At least, that’s what they do until they’re a hundred or so feet from the surface and all heck breaks loose. Usually, thanks to Murphy’s Law, the chaos generally ensues right as you’re trying to un-clip the weight and dropper line from the mainline. Get through that dicey process and thanks to the copper strobe attachment you can then fight the fish without any other major hindrances.

From here on out it’s exactly as you’d suspect: battle the fish in then get ready with the gaff or harpoon. And get ready to make those decks bloody, Mr. Hero Man.