Have you ever wondered why the old cliche, “10% of fishermen catch 90% of the fish,” rings so true? Or maybe, hopefully, you’ve instead asked how you yourself can join that elite 10% club.

The key is understanding that offshore gamefish don’t spend their whole lives at fixed spots on the map – they’re constantly on the move, searching for pockets of food in an otherwise barren expanse of open ocean. In turn, the most successful offshore fishermen use satellite maps of the ocean, such as sea surface temperature (SST) and chlorophyll maps, to track these same pockets of food, focus their efforts on the most productive bite zones, and as a result, catch more fish.

Sea Surface Temperature Maps

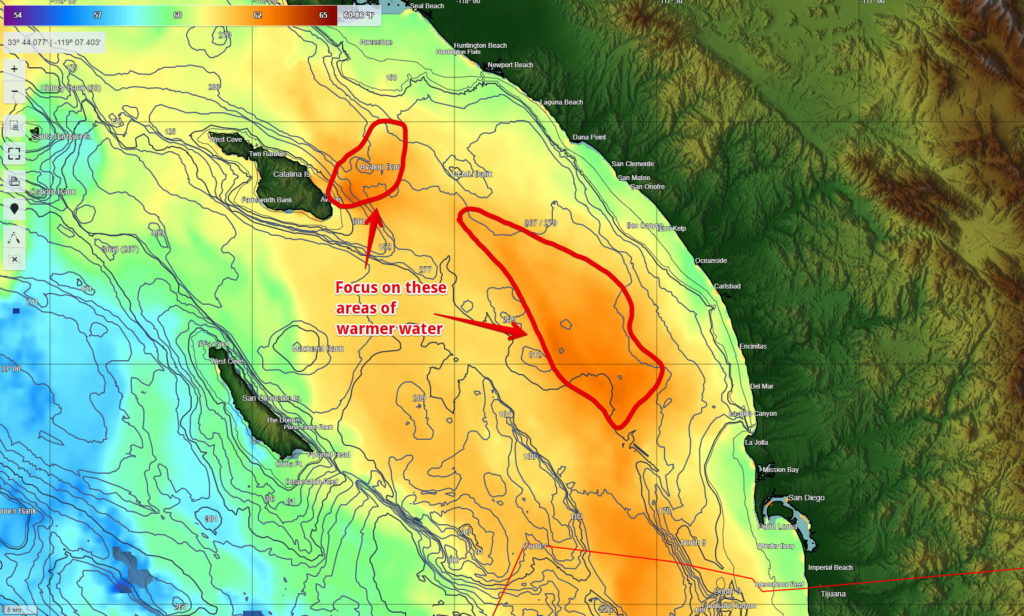

At the most basic level, SST maps can show you where water temps are right for the species you’re targeting. Each species has a preferred temperature range, and pelagic species move around with the water circulation to stay within that range. Using satellite SSTs will help you find the areas that have the right temperature water for your target species – both where you might find them, and where you might be able to get them to eat your bait or jig.

Thermal Range: When regional water temps are near the low end of the preferred range for a species, working the warmest water in the area will be the most productive strategy for finding your target species.

Temperature can also indicate distinct water masses. A water mass is basically an area of water of a certain density, that hasn’t yet evenly mixed with nearby water of different density. Some water masses hold more life than others, and satellite SST maps can show you the boundaries, or breaks, between these different areas.

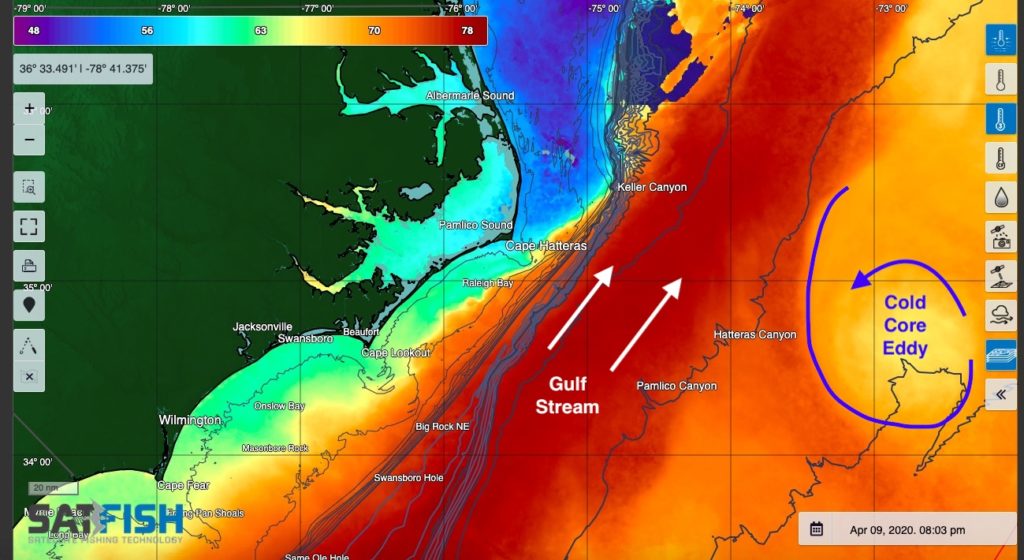

Finally, water temperature can also show other important oceanographic processes. A strip of extra-cold water along the California and Baja coast in the spring and summer is a sure sign of coastal upwelling, which draws cold nutrient-rich water up to the surface and kicks off springtime plankton blooms. Along the same lines, circular spots of cold water on the far side of the Gulf Stream can mark cold core eddies, which also kick off plankton blooms and are a magnet for offshore gamefish.

Speaking of plankton blooms…

Chlorophyll Maps

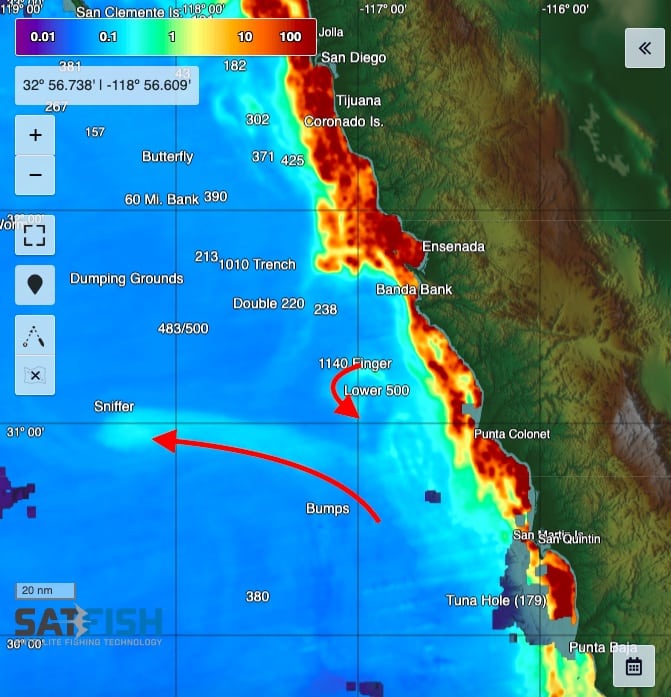

Chlorophyll is where the action is – it’s produced by the phytoplankton at the base of the food chain, allowing life in the open ocean to flourish. Zooplankton eat phytoplankton, small baitfish eat zooplankton, and so on up the food chain to bigger gamefish. The tradeoff is that lots of chlorophyll also makes the water a murky green color, which makes it easier for baitfish to hide from bigger predators.

Chlorophyll: High chlorophyll levels mean lots of food for baitfish and murky green water to hide from predators – but these tuna don’t seem to mind.

Chlorophyll can also be a good indicator of different water masses, hand-in-hand with sea surface temperature. Cold water can hold more dissolved nutrients that plankton need to produce chlorophyll, so you’ll often see areas of cool, green, nutrient- and phytoplankton-rich coastal water extending out as filaments or eddies into clean, warm offshore water. These boundaries can be especially productive zones to look for offshore gamefish.

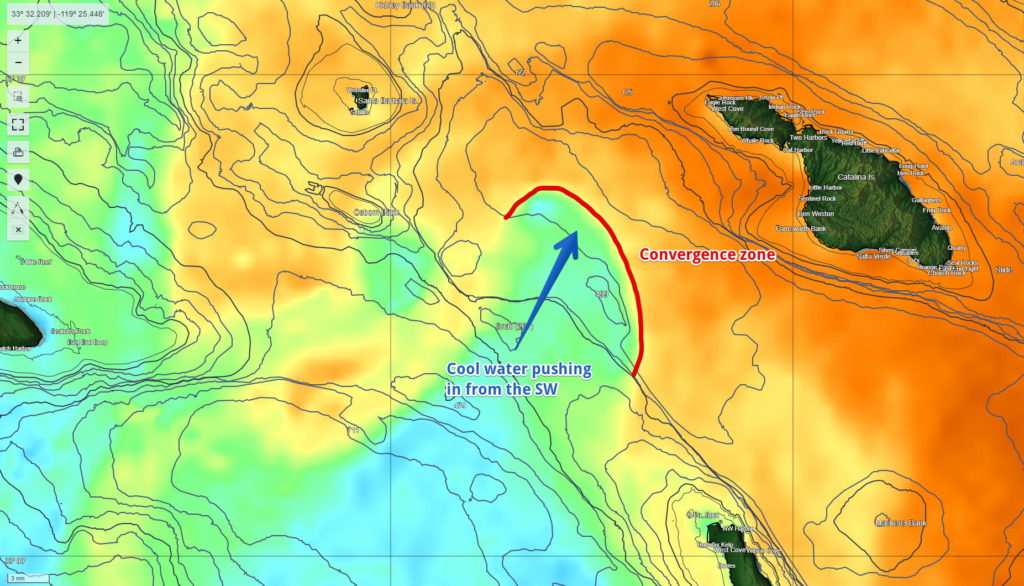

Breaks, Fronts, and Convergence Zones

A common phrase is that fish “stack up” on breaks, or places where the water temperature or color changes quickly over just a mile or two. While this isn’t actually always true, breaks are a still a useful roadmap to finding pelagic gamefish.

Sometimes these breaks form fronts and convergence zones – narrow strips of water that gather drifting flotsam like kelp paddies and weed lines. These, of course, attract baitfish and gamefish like yellowtail and dorado alike. The physical mixing of the two water masses along the break can also create phytoplankton blooms and jump-start the food chain.

Convergence Zones: Temperature breaks can indicate fronts and convergence zones that gather flotsam like kelp paddies – and the fishes that use them for both food and shelter, like yellowtail and dorado.

Even when a break doesn’t form a strong convergence zone, it still marks boundaries of different water masses, some of which will hold more life than others. If you’re trolling along, cross a temp or color break, and find that all the life and suddenly dried up, you’ve likely moved into a different, less-productive water mass. The break didn’t necessarily have all the life right nearby, but it can be a useful marker of where the good, productive water ends. A quality high-resolution satellite image can show you which direction the break runs, so you know which way to point your boat to get back into the productive water.